The overwhelming attention given to the Food and Drug Administration’s announcement of the proposed changes to the Nutrition Facts Label in the United States last week was not surprising. Relatively unchanged since it was introduced 20 years ago, the label is often criticized for being too complex and this “makeover” aims to simplify it and make the information more understandable.

The overwhelming attention given to the Food and Drug Administration’s announcement of the proposed changes to the Nutrition Facts Label in the United States last week was not surprising. Relatively unchanged since it was introduced 20 years ago, the label is often criticized for being too complex and this “makeover” aims to simplify it and make the information more understandable.

And just this week came the announcement by Grocery Manufacturers Association and Food Marketing Institute about the new Facts Up Front nutrition education campaign, which aims to bolster awareness of a front-of-pack labeling system highlighting calories per serving and nutrients of concern. Many food, nutrition, health, marketing, and policy authorities have weighed in on both topics through their respective lens and I’d like the get into the discussion from my vantage point as a registered dietitian and PR professional. Here is a quick 101 to level set this discussion:

• Carbohydrates have four calories/gram; protein has four calories per gram; fat has nine calories per gram.

• Total calories= carbohydrates (grams x 4) + protein (grams x 4) + fat (grams x 9).

• These three nutrients that contribute to calories are called macronutrients and are required in larger quantities, depending on factors including age, gender, and activity level, providing fuel to the body.

• Vitamins and minerals, necessary for the healthy functioning of all body’s systems, are called micronutrients. They are required in smaller quantities depending on factors including age, gender and health status. While they don’t contribute to energy (calories), they do regulate many processes in the body that produce energy.

• The Daily Value is the percent of a nutrient that is provided by a serving of the food and are based on a 2,000-calorie diet. While this caloric level does not represent the needs of all individuals, it is meant to provide context within a total daily diet.

When I consider the proposed changes to the Nutrition Facts Label, it’s from the perspective that the label should not be viewed as a complete roadmap. There are so many factors involved in our food purchasing and eating decisions, and our choices ultimately won’t come down to the information on the label or how it’s designed, formatted or organized. Rather, the label should be viewed as a compass to help guide you in the right direction to making better food decisions. It’s more of a foundational tool to help us understand the caloric and nutritional value of food – and when paired with looking at the ingredients list – can tell us a lot about what’s in our food. Knowledge is power, and the more we know, the better our choices will be.

Here is a look at the key proposed changes to the nutrition label with some thoughts from where I sit, and implications for communications and marketing professionals to consider.

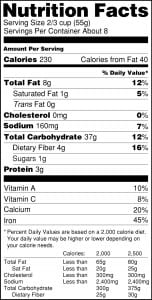

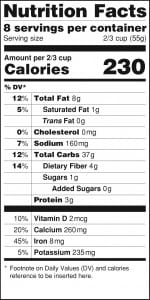

Emphasizing calories and serving sizes with larger, bolder font.

This is my favorite of all the proposed changes from a consumer education standpoint. With this design, the eye is immediately drawn to servings per container or package. There is clarity about how one serving size is defined and how many calories are in that serving. Since all of the information is based on one serving, it provides a greater chance that the shopper/eater will understand and consider the rest of the macro- and micronutrient information before making a decision on what and how much to choose. The distracting and unnecessary “calories from fat” has been removed in the proposed label. Bravo!

Implications: The calories and serving size information has always been there, now it’s just clearer and more tangible. For brands that have a reasonable calories/serving profile, coupled with positive nutrition and a clean ingredients list, this could be an opportunity to highlight a “nutrition bang for the calorie buck” story. Products that are calorically dense per serving will be more recognizable to those who read the label, but it’s not likely these brands would be positioned as a healthful option anyway. Now with calories per serving being larger and bolded, they can no longer hide behind a confusing label.

Updating serving sizes

This change – which would update serving sizes to reflect how much people typically eat during one sitting – has been applauded by many, but I am conflicted. Just because people eat larger portion sizes these days, why should that change what the serving size is listed? The example in this FDA infographic illustrates that a half cup serving of ice cream at 200 calories per serving would appear in the proposed updated label as a one cup serving at 400 calories. Why not continue to promote a serving as half cup? People could select a one cup portion size if they so choose, but defining one serving as a half cup could help promote portion control. People have criticized the current half cup serving size as being unrealistic but I disagree. I have two bowl sizes in my kitchen- I use the six ounce bowls the comfortably fit half cup portions of ice cream and snack size portions of cottage cheese, yogurt and the like, and 16oz bowls for cereal, soup, chili, etc. Research indicates that people eat around 25% less on a 10 inch plate than on a 12 inch plate. I believe that our focus should be on controlling portions at the dinner table and in restaurants (and in nontraditional, not ideal eating environments like cars and desktops), rather than accommodating food guidance to reflect what our obese nation typically eats. This would help curb portions, ultimately cutting calories and putting people on the right path for achieving a balanced diet – even one that includes a responsible portion of ice cream.

Implications: If this proposed change is made in the final regulations, then foods that are calorically dense and typically eaten in larger portion sizes than the serving size indicates will face even more scrutiny. It also provides an opportunity to talk about controlling environmental influences impacting portions selected/consumed, such as the size of bowls, plates, cups and utensils.

Requiring “dual column” labels to indicate both “per serving” and “per package” information for packages that are likely to be eaten at one time

I am completely supportive of this change. Our fingers hitting the bottom of a bag typically dictates when we stop eating, not what is defined as one serving on the label. Research supports that people tend to eat in “units” of pre-packaged food and beverages. So it’s important that nutrition facts are provided for both the serving size and the entire package/container. This may not stop people from consuming the entire “unit” in one sitting, but at least it puts the information about what they’re going to consume front and center.

Implications: Dual column labeling provides an opportunity to talk about mindful eating. We don’t often pay attention to the act of eating, and the hand to bag/hand to mouth action becomes a mindless activity. With more readily available information about what a serving size is vs what the portion size of the “unit” is, brands can communicate the importance of having a greater sense of awareness.

Requiring listing added sugars

I am also conflicted by this proposed change. The body cannot distinguish between naturally occurring and added sugars. Furthermore, analytical testing for added sugars does not exist, unlike for every other item on the nutrition label which can be calculated by analysis (including total sugars). The FDA would require manufacturers to provide the added sugars information upon inspection, which is the only way this proposed change could be enforced. I can appreciate this change was proposed to help provide information to consumers to encourage reducing/avoiding added sugars when making food decisions, but putting a spotlight on added sugars distracts from the larger and more important focus of calories and serving sizes. Added sugars don’t cause weight gain, but they will in the context of too large of a portion/too many calories.

Implications: Beyond the overall cost to updating all labeling once the requirements go into effect, this change will have the greatest impact on brands and general operational procedures of food and beverage companies. For example, record keeping by the manufacturing facilities will be required to support the added sugars declaration. From a marketing perspective, a brand that may have highlighted nutritional benefits of a product in the past – and shoppers may not have been as savvy to recognize ingredients that contain naturally occurring vs added sugars – may need to adjust how far they push the nutrition message if the product contains a perceived high amount of added sugars (I use the word “perceived” because there are no specific recommendations/dietary guidance for added sugars).

Changing what can be called fiber

Currently, processed fibers, such as inulin and maltodextrin, can be counted in total fiber. The changes propose that only intact, unprocessed fiber would appear on the label. I support this change through the lens that it would differentiate whole foods from fiber-fortified foods. On the other hand, fiber-fortified foods do help Americans get closer to meeting fiber recommendations (the majority of men and women don’t meet them), and it’s frightening to think of the impact this would have on one’s calculated daily fiber intake.

Implications: This proposed change would significantly impact how many products often formulated with processed fibers, such as breads, bars and even cookies, can be positioned. If the fiber contributed through fortification cannot be calculated and the products can’t be marketed for their fiber content, I suspect many products will eventually be reformulated to remove these processed fiber ingredients.

It is important to acknowledge that there is a proposed alternate design of the label that indicates which Daily Values to “eat more” of and which to “eat less.” Burkey Belser, the designer of the original 1994 label, brings up an interesting point in The Washington Post about whether nutrition” facts” is the right term to use when this type of change would be prescriptively “telling people what we want you to do – eat more of this, avoid this,” and suggests nutrition “guide” may be a more accurate description. This brings up a fundamental question: Should the nutrition label be only the facts? Grocery Manufacturers Association and Food Marketing Institute’s Facts Up Front can be considered a front-of-pack guide, highlighting the nutrients we don’t eat enough of and those we eat too much of. USDA’s MyPlate is also a guide to making healthier choices supported by the USDA’s Dietary Guidelines for Americans. While there are so many great tools, I know I’d personally like to see a greater societal emphasis on the fundamentals of nutrition and how food works in our body.

A recent popular commercial is filled with so much 80’s nostalgia, many images likely even familiar to Millennials. But how many people recognized the guy in the flesh-colored unitard with organs and tissues strategically placed on the front and back? Slim Goodbody, the Super Hero of Health, made an appearance at my elementary school and on the local news sparking my interested in nutrition and health from a young age. Not everyone goes on to make a career out of it, but possessing a basic grasp of nutrition instilled at a young age would do wonders for empowering people to make healthier choices based on the facts throughout adulthood.

It is important for food marketing and communications professionals to be working closely with their nutrition and regulatory colleagues. It’s unlikely that the nutrition label changes will go into effect for at least a few years, which is interesting because the 2015 Dietary Guidelines could potentially impact elements of FDA’s proposed label changes (the 3nd meeting of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee meeting is next week). While there is so much uncertainty about what will be included in the final regulations and the timing for implementation, one thing can be said with complete confidence – it’s an interesting and exciting time to work in the food world.